| HOME | BLOG | CONNECT | SITE MAP | CONTACT |

Back

Dolphins in the Amazon: Inia geoffrensis

Legends The Amazon River Dolphin is known by many names among the peoples of the South American Rain Forest. These include Inia (Guarayo Indians of Bolivia), from which the genus name is derived16; Boto (Portuguese); Bufeo or Tonina (Spanish); and the "incorrect phonetic spelling Boutu has sometimes been used in English."7 Many of the peoples of the forest have legends about the dolphin. One legend is about their origin. It is said that a small village was having a party, and it got out of control with all the drinking and dancing. The spirits were not pleased, and when the sun went down on the third day, so did the rains. There were enormous floods, and, just before the waters filled the villagers' lungs, they changed into dolphins. The dolphins are essentially "people in the water."14 They are also said to have the ability to change back into people and "gate crash riverbank parties."4 "In these guises, they are often blamed for unexplained pregnancies in virtuous women and for the drowning of careless men."8 The dolphins are also blamed when women go swimming while they are menstruating and become pregnant. The offspring of women thought to be impregnated by dolphins are believed to be magically gifted and often become the tribes shamen.4 Another superstition holds that blindness will result from looking at a lamp that burns oil from a river dolphin.8 The main results of these legends is that it is considered taboo to harm the dolphins, and they are respected by the tribes. This has kept most populations in the Amazon in good condition,16 but the threat of habitat degradation and different beliefs of new immigrants raises concerns.

Inia geoffrensis is just one species of river dolphin in the world. In fact, there is another species in the Amazon. The tucuxi (pronounced too-coo-shee),6 Sotalia fluviatilis, not a true river dolphin, has a range which nearly matches that of Inia geoffrensis, but it also frequents coastal waters.8 The two species are thought to be sympatric,7 which means, despite sharing the same waters, they don't interbreed. "The tucuxi is easily distinguished from its cohabitant, the Amazon river dolphin, by its small, narrow flippers, relatively short beak, and well-developed dorsal fin; the river dolphin has only a low dorsal hump (Fig. 1). The tucuxi...looks much like a miniature bottlenose dolphin."8 The other South American species, not found in the Amazon, is the fransisca or La Plata river dolphin (Pontoporia blainvillei). The other species of river dolphins are in Asian rivers. They are the susus or Ganges River Dolphin (Platanista gangetica), the Indus river dolphin (Platanista minor), and the almost extinct baiji or Yangtze River Dolphin(Lipotes vexillifer). All river dolphins share similar characteristics: elongated beaks, many teeth, reduced eyes, very flexible necks, large, broad flippers, well-developed sonar systems, and a total length of only 5 to 9.5 feet, but these similarities are thought to be the result of convergent evolution.8 Since no river dolphin ventures into salt water, the barriers separating the species seems too great to assume a common ancestor. This has caused some problems with classification. The following table gives the full scientific classification of the Amazon River Dolphin.

Physical Characteristics The maximum size of Amazon River Dolphins ranges from 255 to 274 cm (8.3 to 8.9 feet) for males and around 201 to 228 cm (6.5 to 7.4 feet) for females.7, 9, 13, 16 Their maximum weight ranges from 95 to 160 kg (190 to 350 lbs).7, 9, 13 This is, in general, smaller than their marine relatives. Their rostrums (snouts) are much longer than marine dolphins' and contain 136 teeth. These long, thin beaks, similar to crocodilians', make catching small fishes easier. Most of their teeth are cone-shaped, but they have molar-like teeth toward the back of their mouths which allow them to crush and chew things like armored catfish.

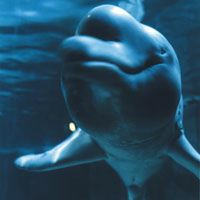

The most striking physical characteristic about Inia and other river dolphins is their pink color (Fig. 2). It is unknown what causes this color, but there are two solid theories. One is that they get the coloring from their diet.4 Like pink flamingoes, the dolphins eat crustaceans in addition to fish. These crustaceans have a pigment in them that is not digested by the birds, but is absorbed and accumulates in their growing feather shafts. This is the same pigment that causes shrimp or crab meat to turn pink when cooked. This could be the reason adult Inia turn pink with age. The other theory is that their age, habitat, and level of excitement determines their color.4, 7 Inia are not born pink, but grayish-blue. The gray is thought to be like the "tan" pigment found in humans. In rivers where light penetrates better, the dolphins tend to keep their gray coloring, at least on their backs where they are exposed to the sun. In murkier waters, the dolphins quickly lose their gray with age. When the gray is gone, the blood flowing in the capillaries just below their skin becomes visible, giving a pink appearance. This would explain why they seem to become even more pink when excited.9 If they flush (increase subcutaneous blood flow) when excited, like humans, they would appear more pink. Whatever the case, their coloring is unique. Of course, another striking characteristic is the smile. It truly is a perpetual smile since Inia do not have the facial muscles to change their expression. Behaviors

Intelligence If nothing else, dolphins have incredibly sophisticated sonar systems, perhaps even more so in river dolphins.14 By bouncing sounds emitted from the "melon" on their forehead off of objects, they are able to "see", even in murky waters. The signals are received by a small bone underneath the chin called the pan bone.4 This is called "echolocation." There have been ten distinct calls from Inia described: echolocation-like runs, grate, creaking door sounds, squawk, screech, bark, whimper, squeak, squeaky-squawk, crack, or jaw-snap.7 It is unclear which, if any, of these are used for communication, and no noises have been linked to behavior.14

Feeding

Reproduction

Lifestyle/Play Habitat and Range Inia are found throughout the Amazon and Orinoco river basins (Fig. 3), in "main rivers, side channels, lakes, floodplain forests, and grasslands, as well as in rivers with strong rapids."7 They are limited at headwaters by impassable rapids and waterfalls, or by the small size of the rivers.7 They are typically found in the murkier rivers of the basins. The darker the river, the pinker the dolphin. Much of the year, they are restricted to the main river channels. But during floods where the water level rises up to 10 meters, their habitat expands into the forest, where they can be found in very shallow water amongst the trees. It is here where their echolocation, hairy rostrums, and flexibility, are even more important. These traits allow them to find food, find their way around, and get out of tight places. Their favorite feeding places are close to the shore, in shallow bays, the forests, or the confluence of two rivers, where the turbulence disrupts the fish and makes fishing easier.7 Unlike the tucuxi, Inia do not venture into salt water, but tucuxi rarely venture into the forest. This makes the range of Inia the largest of all river dolphins.

Future Outlook While the Amazon River Dolphin is not in as much danger as it's Asian cousins, there is some cause for concern. It is not known how many Inia are left in the wild, though the population is thought to be in good condition for now.9 "In the Pacaya-Samiria National Reserve in eastern Peru, dolphins can number as high as 700 during the high-water season,...and the habitat remains plentiful."18 However, there are growing threats to this habitat. Hydroelectric development, agriculture, pollution, and commercial fishing are the biggest threats. Dams and other river developments reduce the number of fish available to dolphins, lower levels of dissolved oxygen, reduce flows of fresh water, and fragment dolphin populations into genetically-isolated populations that, like any genetically-isolated species, become highly vulnerable to extinction.1 Dams also cause changes in the structure of rivers, reducing the sand bars and islands that dolphins prefer. Agricultural problems are two-fold: 1) deforestation reduces the number of fish available for dolphins in rivers by taking away the fruits and seeds that the fish need,16 and it changes runoff patterns, often causing river levels to drop;1 and 2) the chemicals used for farming, mining, and paper milling are part of the pollution problem. The pollution problem is that chemicals in the water, whether from agriculture, or urban and industrial waste, weaken the dolphins' immune systems, leaving them vulnerable to infectious diseases.1 Of course, these chemicals have the potential to affect the entire ecosystem, but little research has been done to determine their levels in the rivers.16 Until recently, people and dolphins could each find enough fish to go around. Now, commercial fishermen are using methods which not only change the equation, but directly affect dolphins and other species. Explosives, hooks, and especially nets used to harvest fish more efficiently are reducing the number of fish available, and directly killing dolphins. Dolphins are mammals and need to breathe air. When they get trapped underwater by a fishing net, they either suffocate, starve, or both. Countries want, and need, to stimulate their economies, but at what cost? If a species at the top of the food chain, like the dolphin, goes extinct, no one really knows the consequences. There could be a huge growth in the numbers of piranhas or some other fish they eat which not only keeps people out of the water, but damages the whole ecosystem. Dolphins may be keeping one species of fish in check that would eat all the other fish the fishermen want if left unchecked. Like everywhere else in the world, it is obvious that pollution levels need to be kept at a minimum for our health as well as other species'. Most agriculture in the rain forest is a short-term, low production endeavor, due to the poor soil quality, and should be regulated if not discouraged. And people should have the right to power, but maybe hydroelectric sources are not the way to go.

This paper is the result of an assignment in C&I 798 - Rain Forest Studies in the Amazon, a class offered by the University of Kansas. The class met near Iquitos, Peru at the confluence of the Napo and Sucusari rivers. © 1997

|